Modern neuroscience would be impossible without functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. The technique is barely 25 years old, but thousands of studies that use it are published each year. When you see headlines such as “Vegetative state patients can respond to questions” or “This is your brain on writing,” you can be sure that fMRI was involved. Last week a new map of the brain based on fMRI scans was greeted as a “scientific breakthrough.”

However, earlier this month, Anders Eklund, of Sweden’s Linköping University, published the latest in a series of papers showing a deep flaw in how researchers have been using fMRI. This flaw, Eklund and his colleagues believe, could ruin the results of as many as 16,500 neuroscience studies over the last 20 years.

The findings have prompted debate and discussion among scientists. But, surprisingly, none of them is freaking out about the fact that two decades worth of understanding could be overturned. In fact, it turns out, the flaws in fMRI are a good example of how scientists are tackling one of the biggest problems the discipline is currently facing: that of making experiments reproducible.

The dead fish that thought

fMRI is a specialized form of MRI, an imaging technique that enables you to look inside the body without having to cut it open. The “functional” bit of fMRI is that it measures changes in blood flow, while ordinary MRI just maps the shapes of tissue. The more active a part of the brain is, the more blood flows to it. By watching which bits are active when someone performs certain tasks or experiences certain stimuli, neuroscientists make deductions about how the brain works.

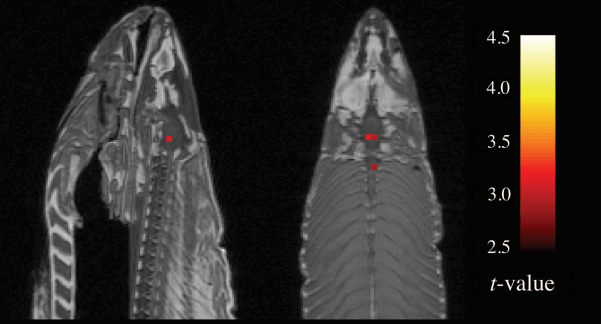

If you put a dead creature in an fMRI scanner, therefore, you should see nothing: Dead things don’t have any blood flow. But in 2009, some researchers put a dead salmon into an fMRI scanner, just to see what would happen.

To their surprise parts of the brain lit up, as if the dead fish were “thinking.”

The reason is that MRI measurements aren’t straightforward to interpret. The signals are “noisy,” in the same way a distant radio station sounds noisy or fuzzy when you try to tune in. In fMRI, which looks for very subtle changes in the signals, the noise can nearly obscure the effect you’re looking for. So fMRI scanners rely heavily on software and statistical tests to eliminate background noise—the standard level of activity you’d see when nothing is happening.

The trouble is, what is “standard” activity can vary from one object to another, or even from person to person. So these software packages and statistical tests have to make a lot of assumptions, and sometimes use shortcuts, in separating real activity from background noise.

Read Full Article – Source: A deep flaw has been discovered in thousands of neuroscience studies — Quartz

Author – Mun Keat Looi